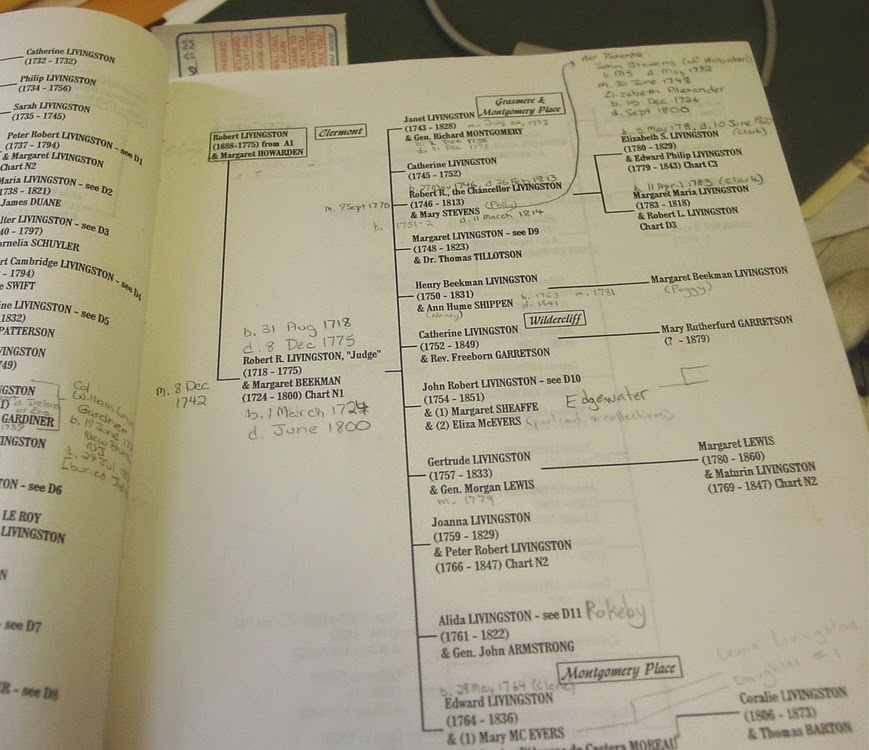

We at Clermont have been on a quest to dispel the myth that Chancellor Robert R. Livingston Jr. was "the Reluctant Revolutionary," as he has been branded by historians. Between giving his fiery commencement speech at King's College, which hinted at rebellion 10 years before the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the recent discovery that he was the bold author behind the "Address to the People of Great Britain," I think it's safe to say that the Chancellor was into the Revolution heart and soul.

![]() Life seemed complete. In addition to the land in Kingsbridge to the south, he bought a farm in Rhinebeck, where Janet would be close to her family. He built a mill (what kind I do not know), and began laying the foundation for their future love nest. In the meantime they stayed in a nice little house in the village.

Life seemed complete. In addition to the land in Kingsbridge to the south, he bought a farm in Rhinebeck, where Janet would be close to her family. He built a mill (what kind I do not know), and began laying the foundation for their future love nest. In the meantime they stayed in a nice little house in the village.

![]() He needed more men. He needed more powder. They were cold and wet in Canada in October. His wife's grandfather died. He found out after the fact that his wife had been sick. Now her parents were sick. Things were not going well.

He needed more men. He needed more powder. They were cold and wet in Canada in October. His wife's grandfather died. He found out after the fact that his wife had been sick. Now her parents were sick. Things were not going well.

![]() Richard wanted desperately to just go home to his wife and his farm. He tried to resign twice, but it was not accepted. The stresses of dealing with people and personalities weighed heavily on him. "I am unfit to deal with mankind in the bulk, for which reason I wish for retirement," he wrote only a few days later on October 9. Their "rascality, ignorance, and selfishness" were too hard to deal with "and keep my temper." That day he was feeling particularly low, and trying to find a way to get home and leave the American Cause behind him, but he was "yoked" to it. A month later on November 13th, he promised Janet again that he would get home as soon as he could find a way to leave.

Richard wanted desperately to just go home to his wife and his farm. He tried to resign twice, but it was not accepted. The stresses of dealing with people and personalities weighed heavily on him. "I am unfit to deal with mankind in the bulk, for which reason I wish for retirement," he wrote only a few days later on October 9. Their "rascality, ignorance, and selfishness" were too hard to deal with "and keep my temper." That day he was feeling particularly low, and trying to find a way to get home and leave the American Cause behind him, but he was "yoked" to it. A month later on November 13th, he promised Janet again that he would get home as soon as he could find a way to leave.

![]() Richard Montgomery was buried in Quebec, and everything he had with him was either sold to other officers, given away, or returned to Janet. Interestingly, Benedict Arnold bought many of his friend's belongings. A pair of wool socks was given to "Dick, the negro boy," A gold watch was returned all the way to Janet.

Richard Montgomery was buried in Quebec, and everything he had with him was either sold to other officers, given away, or returned to Janet. Interestingly, Benedict Arnold bought many of his friend's belongings. A pair of wool socks was given to "Dick, the negro boy," A gold watch was returned all the way to Janet.

But perhaps it was this virulent commitment that gave his sister's brother Richard Montgomery the final nudge he needed to help build and lead the army of the rebellious colonists.

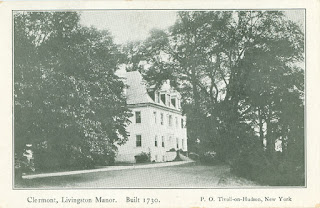

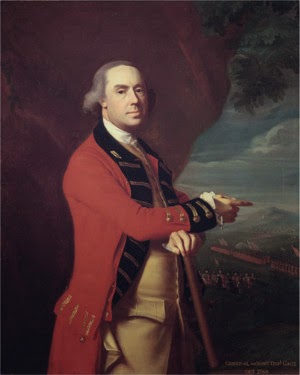

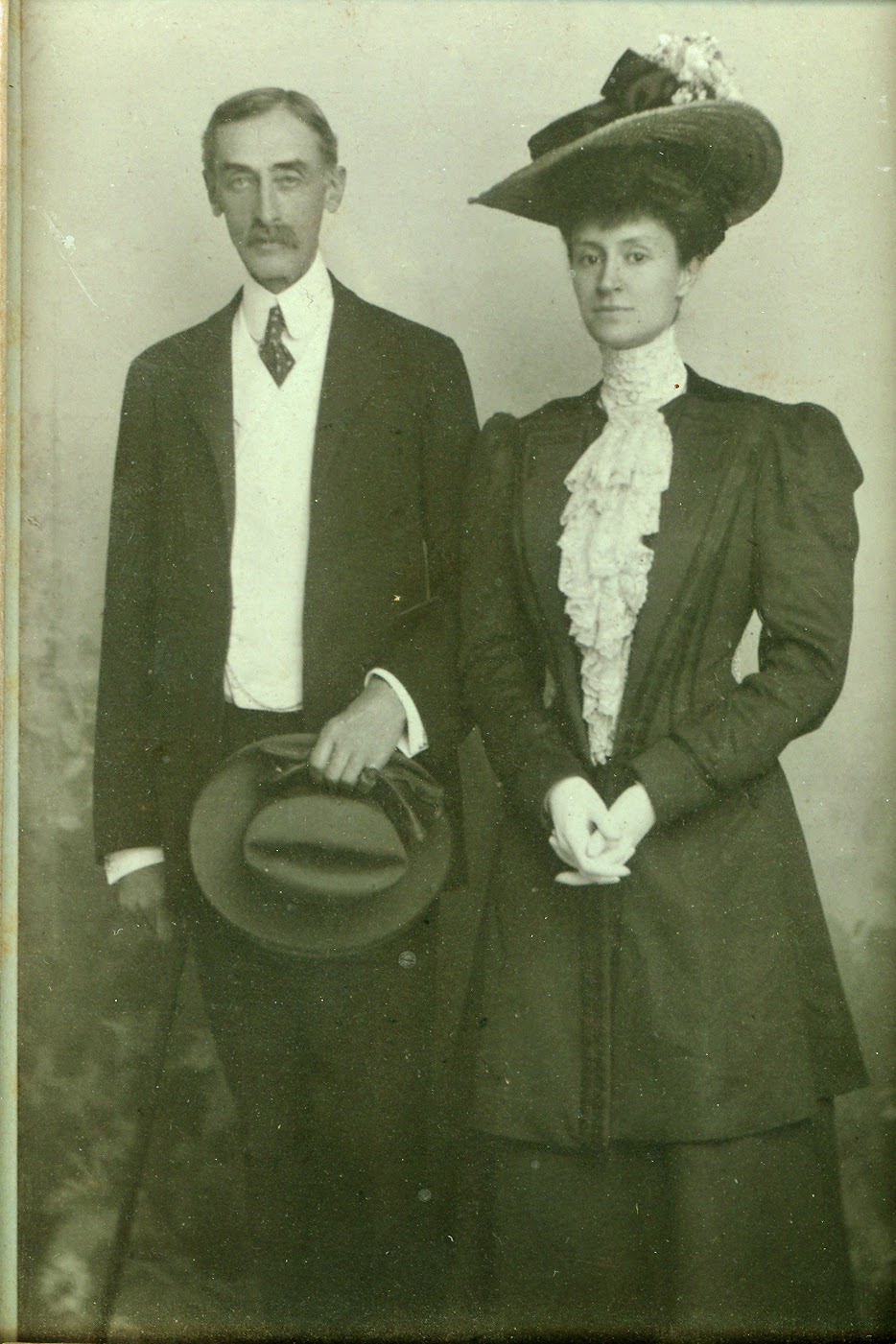

Richard had met the Livingston family (and his future wife Janet) during the French and Indian War, when he served as a Captain in the 17th Regiment of His Majesty's Army. According to an 1876 biography, he was on his way "to a distant post and had come ashore with the officers of his company at Clermont..." (possbily Ticonderoga). Happening sometime during the later 1750s or as late as 1760, this would have been just as Janet was reaching marriageable age, and what eligible young lady doesn't like a dashing company of well-dressed officers at her doorstep?

That was just a blip in time though. Richard went on with the war, went back to Ireland, and tried to pursue his military career. It was a bust. His sympathies for the Colonies and rejection of the Stamp Act were too well known. He was passed over for promotion to Major, got mad, and resigned to go back to the fertile promises New York. He purchased a farm in what is now the Bronx and renewed his conversations with Janet Livingston.

It had been more than 10 years since their first meeting, but she was still single. Not that she couldn't get a good marriage proposal. The New York Public Library is in possession of a letter from Janet turning down a proposal from Horatio Gates (yet another officer in the English army). Janet was now 30 years old and apparently waiting for just the right proposal.

After checking with her father in May (and Janet's father checked with her mother first--because nobody messes with Margaret Beekman Livingston), Richard finally got to marry Janet in July of 1773.

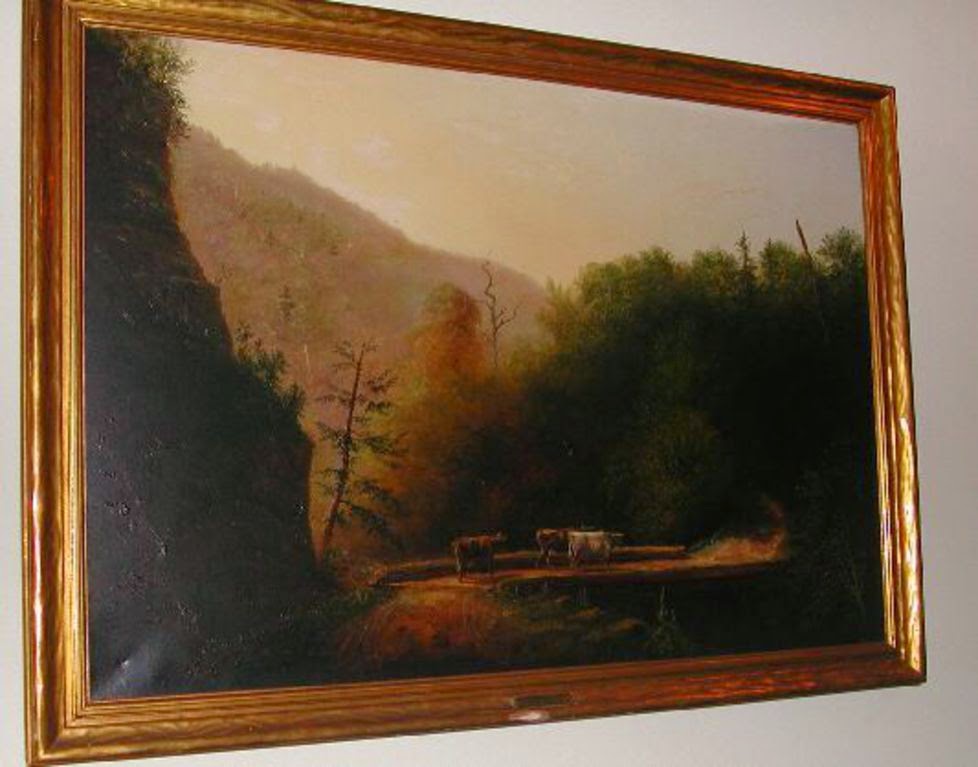

Life seemed complete. In addition to the land in Kingsbridge to the south, he bought a farm in Rhinebeck, where Janet would be close to her family. He built a mill (what kind I do not know), and began laying the foundation for their future love nest. In the meantime they stayed in a nice little house in the village.

Life seemed complete. In addition to the land in Kingsbridge to the south, he bought a farm in Rhinebeck, where Janet would be close to her family. He built a mill (what kind I do not know), and began laying the foundation for their future love nest. In the meantime they stayed in a nice little house in the village. But within two years, the political climate in the colony was getting more unstable. According to his wife, Richard was "surprised" with a nomination to the Committee of Fifty that met in April 1775 in New York to organize protests against the increasingly-strict and punitive legislation coming out of England. The Committee (whose size swelled rapidly) included his brother-in-law Robert, several other Livingston family members and another close friend of Robert's by the name of John Jay.

Richard went out of a sense of duty. Duty to his new homeland? Duty to his good friend Robert? He balked at the idea of violent rebellion against Britain but believed that the Empire's treatment of the colony was wrong. Either way, he apparently didn't think much of his contribution on the committee. He was cynical and frustrated by all the talking that politics required of him. Later when the rebellious colonists then began raising an army lead by French & Indian war vets (like George Washington), his experience proved proved more applicable.

He mulled his decision over, and finally, being unable to find the words to tell his wife, he did it with a gesture. He went to her with the black black ribbon cockade for his soldier's hat and asked her to sew it on for him. Her reaction was to be expected; she began to cry. In her memoirs she remembered his explanation this way:

"Our country is in danger. Unsolicited, in two instances, I have been distinguished by two honorable appointments. As a politician I could not serve them. As a soldier I think I can...My honor is engaged."

He was so torn by the force of duty and the desire to remain home with his wife and farm that he refused to even look back at his house when he left it in June of 1775. His brother-in-law Edward (then 11 years old) remembered him musing sadly "'Tis a mad world, my masters, once I thought so, now I know it." Richard's words carried extra weight as he not only summed up the chaos of the oncoming war and breakdown of civil order, but cited an English proverb with at least a century of history behind it.

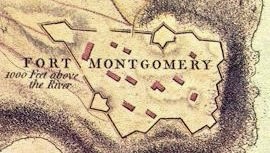

It's no surprise that Richard's previous years in "the Greatest Army in the World"--as the English forces were known--left him lacking faith in the abilities of the inexperienced and unprofessional Colonists that signed up to be in his brigade. He certainly wasn't alone in this, and it was only the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17th that gave them the encouragement they needed to trust the farmers, mechanics, and workers who signed up.

Nevertheless, he still scoffed at their courage, saying that they "ran at the shake of a leaf" or were all bravado until some real conflict threatened their lives. He once wrote to Janet, "I am ... so exceedingly out of spirits and so chagrined with the behavior of the troops, that I most heartily repent undertaking to lead them." Another time he worried that "the lower class of people...have been intimidated much by our weakness."

He needed more men. He needed more powder. They were cold and wet in Canada in October. His wife's grandfather died. He found out after the fact that his wife had been sick. Now her parents were sick. Things were not going well.

He needed more men. He needed more powder. They were cold and wet in Canada in October. His wife's grandfather died. He found out after the fact that his wife had been sick. Now her parents were sick. Things were not going well.  Richard wanted desperately to just go home to his wife and his farm. He tried to resign twice, but it was not accepted. The stresses of dealing with people and personalities weighed heavily on him. "I am unfit to deal with mankind in the bulk, for which reason I wish for retirement," he wrote only a few days later on October 9. Their "rascality, ignorance, and selfishness" were too hard to deal with "and keep my temper." That day he was feeling particularly low, and trying to find a way to get home and leave the American Cause behind him, but he was "yoked" to it. A month later on November 13th, he promised Janet again that he would get home as soon as he could find a way to leave.

Richard wanted desperately to just go home to his wife and his farm. He tried to resign twice, but it was not accepted. The stresses of dealing with people and personalities weighed heavily on him. "I am unfit to deal with mankind in the bulk, for which reason I wish for retirement," he wrote only a few days later on October 9. Their "rascality, ignorance, and selfishness" were too hard to deal with "and keep my temper." That day he was feeling particularly low, and trying to find a way to get home and leave the American Cause behind him, but he was "yoked" to it. A month later on November 13th, he promised Janet again that he would get home as soon as he could find a way to leave. In late November he found a way to return to Rhinebeck in the winter, planning to be there in January, and it raised his spirits to see his wife in their "new house" (Grasmere, I assume). "I live in hopes to see you in six weeks," he wrote. "Gentle" weather made the following weeks more bearable, and in his final letter to Janet on December 5th he mused "may I finally have the pleasure of seeing you in it [the new house] soon!"

After a hard journey north through Canada, the capture of Quebec was to signal his return home. His spirits lifted as he could finally see the light at the end of the tunnel, he even managed a little levity in his letters. As the Christmas holidays approached, he mused to his friends that only his sense of duty kept him going, that his only ambition was a safe and happy farm. The thought of returning to it warmed his spirit as he roused his fatigued troops to attack Quebec, personally leading the charge up the hills--and he was almost immediately cut down by cannon ball. The attack fell apart. He would never return to his farm and beloved Janet.

For his wife, that year must have been an impossible one: at 32 years old she had lost her Livingston grandfather in July, and her Beekman grandfather followed in December. Only a few days later, her father died suddenly at Clermont on December 8th. And while she waited for the comfort of her husband's return in the new year, her brother the Chancellor was busy writing the letter that would tell her the worst news of all; her beloved husband was dead.

So of all the Revolutionaries out there, it seems that Montgomery most deserves the title of "Reluctant." While in the Chancellor's case (however misapplied) it has been used to almost diminish his considerable contribution, in Richard's case it seems rather to contribute both a sense of tragedy and honor to his sacrifice. In spite of a considerable desire to remain at his own hearth, Richard's sense of duty to propelled him to protect his new country (thus forsaking the King and country for whom he had previously fought) and lead him far from home. With few supplies and men in whom he had little faith, he continued to long for his wife and his plow, but he wouldn't desert his post without first ensuring that the cause could continue without him.

Of course, the real twist of the knife is that he was only days or weeks away from going home.

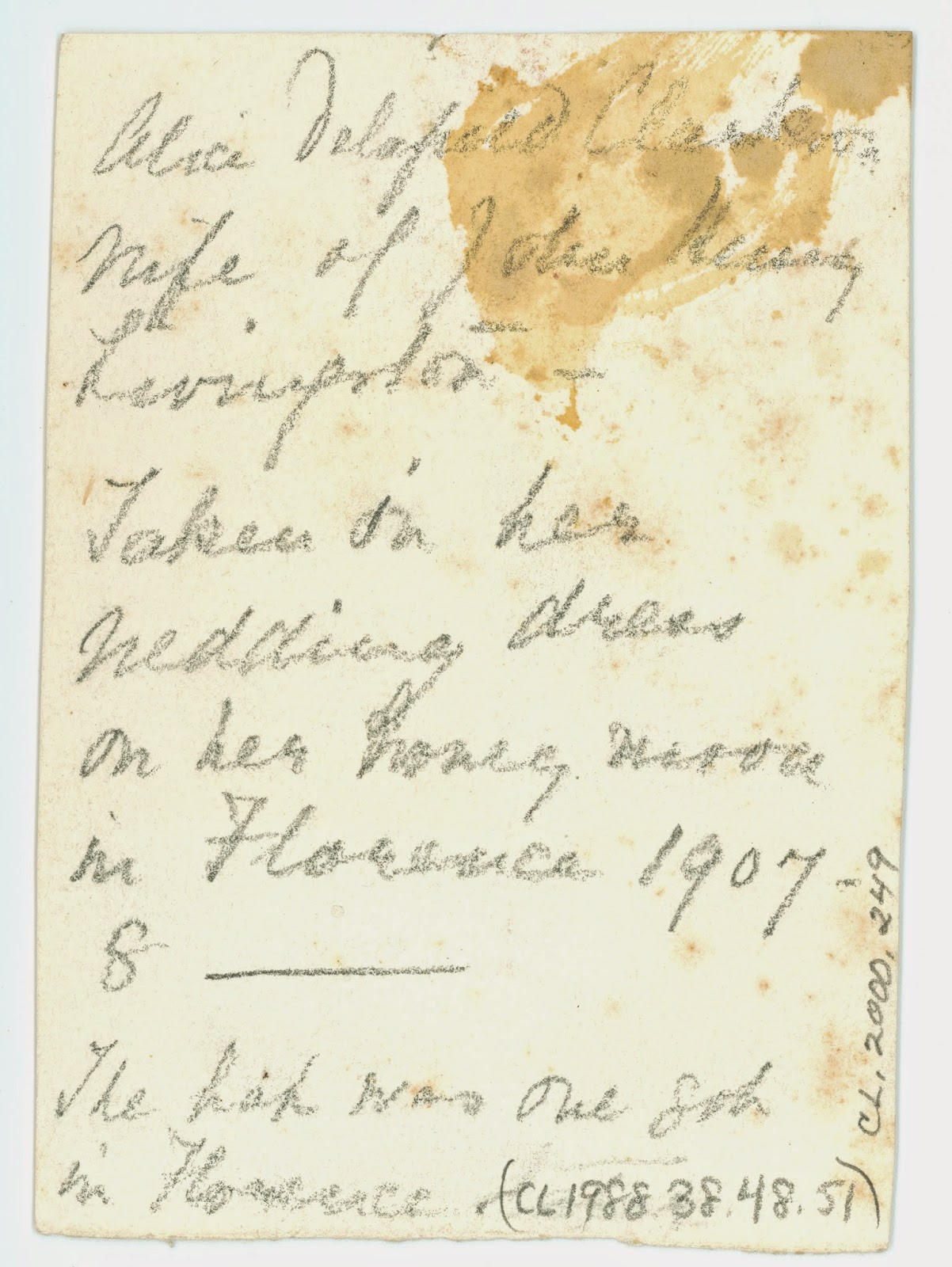

Like her mother, Janet never remarried. As a wealthy widow, she most likely had the opportunity, but instead she filled her life with family and friends. She wrote sometimes that she felt like her widow status made her an outsider or fifth wheel but there was no replacing a relationship that had taken her until age 32 to find in the first place.

Richard Montgomery was buried in Quebec, and everything he had with him was either sold to other officers, given away, or returned to Janet. Interestingly, Benedict Arnold bought many of his friend's belongings. A pair of wool socks was given to "Dick, the negro boy," A gold watch was returned all the way to Janet.

Richard Montgomery was buried in Quebec, and everything he had with him was either sold to other officers, given away, or returned to Janet. Interestingly, Benedict Arnold bought many of his friend's belongings. A pair of wool socks was given to "Dick, the negro boy," A gold watch was returned all the way to Janet.Forty-three years later Governor Clinton sent Janet a copy of the act that described the planned removal of Montgomery's remains from Canada to New York. Overcome by emotion as she watched the boat pass by her new house at Chateau de Montgomery (Montgomery Place), Janet fainted dead away. It was the closest she had been to her husband since the day he left her, promising "You shall never have cause to blush for your Montgomery."

.jpg)