For a long time all I knew about

Clermont Livingston was that he was named after the house and that he kept a very detailed

garden journal.

Clermont Livingston (pronounced like "Clement") was the head of Clermont

the estate from 1844 when his father died and officially through his own death in 1895--though during the last few decades, the family mansion was largely occupied by his children and their families, while he moved over to neighboring

Arryl House. I have long thought of Clermont through his son's eyes, since at Clermont we focus a great deal on that generation. But of course he wasn't born old, and he is best connection to our Victorian-era past.

He was the privileged

son of a wealthy

NY statesman, the inheritor of the lost Steamboat legacy (the monopoly was broken in 1824), and the grandson of a

founding father. There was a lot of family pride.

![]() |

| Clermont in 1796, overlooking the Hudson River |

But Clermont grew up to be much more reserved than other Livingston heads of household. He was the only head of Clermont who never obtained a public office. Who was this guy? And why is era of leadership at Clermont the quietest in our records?

Clermont, the boy, was born in 1817 and grew up splitting his time between the Livingston estate on the Hudson River, Albany, and presumably New York City. By the time he was born, his parents had lost four of his elder siblings, all under the age of five, and two years later in 1919 his teenage sister Mary died as well. The surviving siblings that Clermont grew up with were:

-Margaret, 9 years his senior

-Elizabeth, 4 years his senior

-Emma, 2 years old, but died in 1828

-Robert E., 3 years younger

-Mary (again), 6 years younger

![]() |

Betsy Stevens Livingston

was Clermont's mother |

When Clermont was 12, his mother

Betsy passed away at the age of 49.

At some point his father married Marry C. Broome, perhaps a contentious decision considering that Mary (b. 1810) was actually

younger than his oldest daughter Margaret (b. 1808), and there are a few indications of weak relations which I'll mention later.

So Clermont's early tween years were marked by some pretty big upheavals. Though certainly not uncommon for the time, the death of sister, followed quickly by that of his mother, and then accepting a new step mother couldn't have been easy for a kid. Nevertheless, a little collection of 9 letters from his bachelor years suggest that Clermont had built some pretty close relationships with friends and family.

In 1835, at age 17 he was corresponding with his brother-in-law Edward Ludlow (Elizabeth's husband) about finding a housekeeper for their New York home, current events, and sharing gossip about neighbors and acquaintances. He also kept up with his older sister Margaret, but he complained that Elizabeth did not write him directly. Margaret's letters to her younger brother were newsy and familiar. She referenced

New Year's Day Visiting (interestingly using her sister Mary's first name, but giving the formal and distant title of "Mrs. Livingston" to her step mother). She lamented that there was not enough snow for sleighing. She bid her brother write her about their activities in Albany, where their father was a New York State senator. And she updated him on

her day-to-day:

I have been very busy hunting up little knick nacks for the children's stockings, dressing dolls so Christmas day was a very merry one for the children, during the holidays they do nothing but play, at this moment there is such a noise that I scarcely know what I am writing about...and just now [they] nearly upset the ink stand over this paper..."![]()

He talked about riding steamboats to and from Albany with his younger brother Robert in the summer to make "a few perchase's (sic)." And cousin Edward Macomb reminded him of a promise Clermont'd made last fall when riding the steamboat up from New York that he'd be groomsman at an upcoming wedding. Edward assured Clermont that although he did not yet know

who the bridesmaids would be, "they will be without doubt very charming."

Clermont's relationship with Edward seems to have been one that was a little less formal than the ones he shared with his sisters. The reference to "charming ladies" suggests a shared interest in women, and in a letter the next month (in February after the wedding) Edward described a "delightful dinner party at Mrs Gates" where "each gentleman had a fair lady on his right and left..." While Edward was planning to move to Washington for business, he mused, "I have had many pleasant days at your delightful residence & hope to have many more." Oh--and by the way, there's another wedding coming up in April, "when I suppose we shall have the pleasure of seeing you again."

Although the year is uncertain, Clermont responded to a "Ned" in February--and it seems possible that it was to Edward Macomb--when he wrote lamenting the news that "Strats" had "been so soon allured by the charms of the fair sex to desert the ranks of the bachelors." He then wrote a little ditty, expecting his friend to set to music himself. The slightly ribald poem ended with the lines:

Now on Matrimony's stream he floatsMay he in short have his sportBeneath the shade of the petticoats

And he signed it "Bunderbus."

By far the most jovial letters came from Clermont's friend William Tallmadge. I can't seem to find anything about this young man, but he seems to be a peer who knew Clermont from their time in Albany, where Clermont's father served in state government. He may even have been related to contemporary Albany statesman and abolitionist James Tallmadge Jr., but I can't be sure.

Anyway, William was full of jokes, and his letters are tinged with a youthful and good-natured sarcasm. "This City is as void of news, as Connecticut is of Democrats," he wrote in April of 1838. He too gossips about the interesting ladies in their acquaintance: "I saw Miss Caroline King yesterday in the street, she continues to look very handsome, and was particularly interesting..." "Miss Boswick is very well at present." And he signs off his letter of April 27 remembering his care for Clermont's parents and then, inexplicably, "Give my best respect to friend Robert and tell him not to hang himself."

Subsequent letters continue to reference young ladies. "Miss Skinner has just arrived in town and of course I shall treat her as she ought to be, she will visit our house this evening, and if you were here we might make quite a pleasant party..." he wrote in July of the same year..

The two shared more than just an interest in The Ladies though. When William took ill in 1840, Clermont's letter revived and comforted him: "I assure you...I have never received a word from a friend which gratified me so much..." It seems the friends had made plans for yet another excursion to Saratoga Springs, but Tallmadge's "Billious attack" made him too weak and sick to join his friend. Even sick, though, William was not without jokes:

![]() |

Clermont Livingston eventually

grew his own "astonishing whiskers." |

How is Mr. Robert, is he flourishing - has he that huge pair of whiskers you were speaking about - if he has, tell him to keep them until I come up. I have a pair that may astonish the natives in your part of the country.Clermont's life was not all ladies. Both Margaret and Tallmadge mention Clermont being busy with his studies (although Margaret follows it up with "dancing in the evening").

Clermont continued to live with his father, at least through 1840; letters to him from his friend Tallmadge were address care of his dad Edward P. Livingston. But he sometimes stayed with his sister Elizabeth and her husband Edward Ludlow in New York City, where the night life was surely more interesting. Ludlow's letter to his brother-in-law in 1835 or 1840 (the two years in this timeframe in which December 10th, fell on a Thursday) indicated that he hoped Clermont and younger brother Robert would come stay with them again that winter. And later in 1841, Clermont spent the Christmas holidays there again.

When Clermont's father died at the end of 1843, it was time to settle down. Edward P. Livingston

died intestate, making the process of sorting the estate decidedly more complex. There seems to have been some confusion about what belonged to the step mother Mary Broome and what should have gone to Clermont's younger sister Mary. Although the Widow Mary had taken a sizable inventory of household goods, little or nothing was left for the 21-year-old daughter. If the relationship with the Livingston children's step mother had been strained before, having to engage the legal consultation of cousin Livingston Livingston (no, it's not a typo. That's really his name) three months later probably didn't help matters. For the record, cousin Livingston said Mary the Widow should have given a lot more to Mary the daughter.

In 1844, it seems that Clermont's youth was done, and it was time to settle down and become a gentleman farmer. He got married that year to his pretty cousin Cornelia Livingston from Oak Hill and got down to the business of running the estate. He saved his family estate from the

Anti-Rent mess by selling off some land. He saw to it his little sister Mary was taken care of (since her step mother was gone by now), and became the de facto head of the Livingston family at Clermont.

But of course, there was much still ahead of him.

![]() Decorating the mansion for Halloween takes quite a bit of planning. You see, we work hard to keep it all looking appropriate for the 1920s, and that means researching the right look and where on earth to get the right products. Luckily for us, the aesthetic for the 1920s called for tons of crepe paper, streamers, and balloons, all carefully put together to form hanging confections of decoration.

Decorating the mansion for Halloween takes quite a bit of planning. You see, we work hard to keep it all looking appropriate for the 1920s, and that means researching the right look and where on earth to get the right products. Luckily for us, the aesthetic for the 1920s called for tons of crepe paper, streamers, and balloons, all carefully put together to form hanging confections of decoration. ![]() After eight years, we've gotten pretty good at it, and we're starting to get more into it. Last year, we worked around a Edgar Allen Poe theme with "The Raven." Quotes posted above doors and windows complemented our many feathered ravens (okay, they were really crows--but it's pretty hard to find affordable decorative ravens right now).

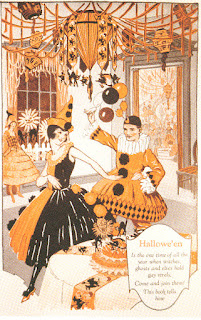

After eight years, we've gotten pretty good at it, and we're starting to get more into it. Last year, we worked around a Edgar Allen Poe theme with "The Raven." Quotes posted above doors and windows complemented our many feathered ravens (okay, they were really crows--but it's pretty hard to find affordable decorative ravens right now). ![]() And voila! our theme is now a Commedia dell'Arte Masquerade with Harlequins, Columbinas, Pierrots--all filtered through the lens of the 1920s. It turns out these were pretty popular costumes beginning in the first part of the century, and they show up a lot during the period if you know what you're looking at. The diamond motif can be found all over Halloween imagery of the period, and the pom poms, neck ruffs, and masks were usually enough to give the viewer the desired impression.

And voila! our theme is now a Commedia dell'Arte Masquerade with Harlequins, Columbinas, Pierrots--all filtered through the lens of the 1920s. It turns out these were pretty popular costumes beginning in the first part of the century, and they show up a lot during the period if you know what you're looking at. The diamond motif can be found all over Halloween imagery of the period, and the pom poms, neck ruffs, and masks were usually enough to give the viewer the desired impression.![]() So now it's just putting our plan into action: finding fabrics and paper, making pom poms and neck ruffles. There is so much left to do!

So now it's just putting our plan into action: finding fabrics and paper, making pom poms and neck ruffles. There is so much left to do! Decorating the mansion for Halloween takes quite a bit of planning. You see, we work hard to keep it all looking appropriate for the 1920s, and that means researching the right look and where on earth to get the right products. Luckily for us, the aesthetic for the 1920s called for tons of crepe paper, streamers, and balloons, all carefully put together to form hanging confections of decoration.

Decorating the mansion for Halloween takes quite a bit of planning. You see, we work hard to keep it all looking appropriate for the 1920s, and that means researching the right look and where on earth to get the right products. Luckily for us, the aesthetic for the 1920s called for tons of crepe paper, streamers, and balloons, all carefully put together to form hanging confections of decoration.  After eight years, we've gotten pretty good at it, and we're starting to get more into it. Last year, we worked around a Edgar Allen Poe theme with "The Raven." Quotes posted above doors and windows complemented our many feathered ravens (okay, they were really crows--but it's pretty hard to find affordable decorative ravens right now).

After eight years, we've gotten pretty good at it, and we're starting to get more into it. Last year, we worked around a Edgar Allen Poe theme with "The Raven." Quotes posted above doors and windows complemented our many feathered ravens (okay, they were really crows--but it's pretty hard to find affordable decorative ravens right now).  And voila! our theme is now a Commedia dell'Arte Masquerade with Harlequins, Columbinas, Pierrots--all filtered through the lens of the 1920s. It turns out these were pretty popular costumes beginning in the first part of the century, and they show up a lot during the period if you know what you're looking at. The diamond motif can be found all over Halloween imagery of the period, and the pom poms, neck ruffs, and masks were usually enough to give the viewer the desired impression.

And voila! our theme is now a Commedia dell'Arte Masquerade with Harlequins, Columbinas, Pierrots--all filtered through the lens of the 1920s. It turns out these were pretty popular costumes beginning in the first part of the century, and they show up a lot during the period if you know what you're looking at. The diamond motif can be found all over Halloween imagery of the period, and the pom poms, neck ruffs, and masks were usually enough to give the viewer the desired impression.